Elisha Shapiro (aka Nihilist Field Marshal Shapiro) is a Los Angeles-based

media prankster and conceptual artist. He has been creating his

neo-dadaesque public spectacles for the past 15 years and first

came to public attention with his 1984 Nihilist Olympics. The

Olympics were followed by a Nihilist campaign for President in

1988 and a Nihilist campaign for LA County Sheriff in 1994. In 1999 he staged Nihilism Expo '99, a world's fair for nihilists. He

currently hosts a monthly cable TV show called Nihilists' Corner.

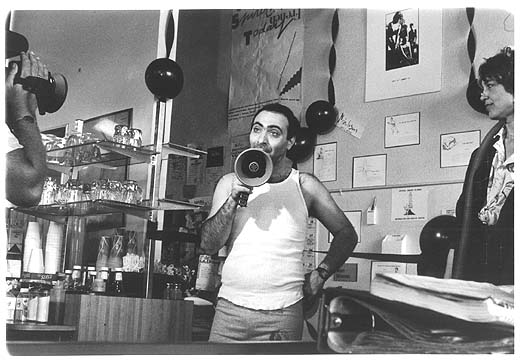

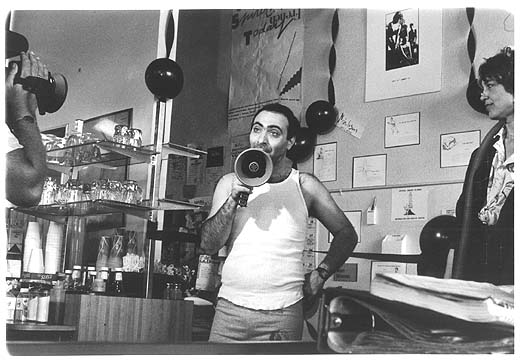

VOTE NIHILISM '94

Shapiro For Sheriff Campaign HQ Opening

Zero One Gallery, LA, February 12, 1994

I DON'T BELIEVE IN ANYTHING;

WHY DO YOU?

KPFK radio, Los Angeles - Soundings, Aug. 7, 1990;

Apr. 2, 1991; Nov. 9, 1993

LA Perspectives Festival, UCLA, April 26, 1991

LA Cultural Affairs Grant, July

1991

LACE, LA, November 14, 1993

Nihilism Booth, Westwood Village, May 1992

Freewaves October Surprise, October 17, 1992

FAR Bazaar, December 4, 1992

NIHILISM EXPO

Announcement Press Conference

SMARTS summer performance series, Santa Monica, August

5, 1989

Nihilism Expo Cancellation Gala - performance,

Zero One Gallery, Los Angeles, September 1, 1990

VOTE NIHILISM '88

Announcement Event, July 4, 1987, Downtown

Los Angeles

Nihilist Party Nominating Convention, August

12, 1988, Santa Monica

San Diego Airport Event, October 1, 1988

San Francisco Airport Event, October

8, 1988

THE HOLY WARS, Los Angeles, April 1985, Los

Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions

1984 NIHILIST OLYMPICS, Los Angeles,

1981-84, 40 performances at: city locations,

Gorky's Cafe, Lhasa Club, Club Lingerie, SPARC

FLATLANDS, performed/collaborated, Pilot

Theater, Los Angeles, July 1983

ELIGIBLE BACHELORS with Linda Albertano, performed,

Los Angeles/San Pedro, 1983

SWAY BACK, performed/collaborated, The

House, Santa Monica, March 1982

REST AREA # 17, performed, October 1981, Industrial

St Space, Los Angeles

THE FIELD MARSHAL'S CHILDHOOD

One afternoon I had closed myself in when my older brother, back from his day in the third grade, insinuated himself into my hall.

"Elisha, I think there's something in your eye." he said, reaching for my right eye. He gently tugged on my lower lid, pulling it away from my eyeball. Somewhere, outside the field of my vision, he held a wire clothes hanger. Then he simply hung it on my lower eyelid.

My father appeared quickly when he heard the screams. He removed the hanger and slapped my brother a few times.

That summer, it was 1958, my parents piled us all into the Hudson, and we drove cross-country. We spent a while at Lake Michigan, and on our way home, we stopped at Little America in Texas. I remember Little America as a hotel for families, or maybe an amusement park, or possibly both.

While we were at Little America, my parents gave me a party for my fifth birthday. It was a nice party, but more importantly I got a cowboy suit as a gift. This wasn't just any cowboy suit--it included a shirt, pants, hat, boots, holster and gun. And it was all red with white piping. When I put it on and saw myself in the mirror, I was stunned by how grand I looked. I think it was the best birthday present I've ever received.

Several months later, back at home, we no longer had the Hudson. The white, round, old-fashioned car was replaced by a modern, red Plymouth station wagon with fins.

The whole family was loaded into the wagon, going somewhere, when there was a siren and flashing lights. My dad pulled over and a very serious and tense policeman came over. From low in the back seat, I watched as he began grilling my dad, asking him all sorts of questions. Then he said, "Do you know you have a gun on your car?"

My father was non-plused.

The policeman eyed my father suspiciously. Then he walked to the rear of the car and picked up my gun off the right fin. When he realized it was a toy, we could see him relax.

"This belong to one of you?" he said to my brothers and me in the back seat. My father took the gun and passed it back to me as he apologized to the policeman.

In the house we lived in at that time, the kid's bathroom had a regular bath tub. But in my parents' bathroom, they had a bath and shower combination with sliding glass doors. Sometimes they'd let me take a shower in their bathroom. I liked the enclosed nature of their facilities. I'd sit in the tub with the glass doors closed, with the shower on, and sometimes with the bath running. I could play that way for as long as they'd let me.

One day I got an idea. I got all the washcloths I could find, and a couple of towels. I turned on the bath water all the way. Then I started using the wash clothes and towels to block all the cracks in the glass doors which might let water out. After a while, the water was to the top of the tub. Some water leaked out at the drain stopper lever--so I blocked that with a wash cloth. Soon the water was creeping up the glass doors. I was standing. Then I started treading water.

It was like my own swimming pool, or my own aquarium. I happily splashed around, and my washcloths seemed to be holding.

My mother, who was several rooms away, noticed water flowing down the hall and into the living room.

The next thing I knew, she burst into the bathroom. She looked at me, a bit puzzled. Then she became agitated, shouting for me to turn off the water.

At this point, turning off the water required a pretty deep dive. Unused to performing manual tasks while under water, it took me a few tries.

She wasn't satisfied. She urged me to go back under to open the drain. I reluctantly obeyed.

When she got me out and dried off, she sternly told me not to do that again.

Maybe a year after this, I remember getting up one morning to find my mother sitting at the kitchen table with a big piece of raw meat pressed to her face. When she took it away, most of her face underneath was swollen and the same purple as the meat. She was in her bathrobe, having come home from the hospital during the night while I slept. As close as I could piece the story together at the time, this is what happened. She was driving home from a class at night. She was tired and fell asleep. Then the red Plymouth station wagon went off the freeway overpass on which she was driving. The car burst into flames, and a passing stranger dragged her unconscious body from the wreckage. My mother was bruised like I didn't know people could bruise. But that's all that happened to her. There was a small article about it in the Riverside Press Enterprise. My mother's rescuer was hailed as a hero.

All this happened a couple of days before Mother's Day, and in my kindergarten class, our assignment was to make Mother's Day cards for our mothers. Considering these dramatic events, I resolved to render them as faithfully as possible on my mother's card.

One Sunday afternoon I was sitting in our front yard among the fustucca plants, pulling weeds as my father had instructed me. Molly Boblette was there. Molly lived two houses down from us and was the second of four children. She was older than I was by about five years . I didn't really notice when or from where she had come. She saw a hoe leaning against the house were my father had left it. She picked it up and came over to where I sat. Leaning on the hoe, she said, "What are you doing, Elisha?"

"Weeding."

"Do you dare me to hit you on the head with this hoe?"

I had been in this situation before, having older brothers. I knew there was no correct answer to her question. I just looked at her, trying to figure out what it was she wanted from me.

"Okay, then." she said, awkwardly picking up the hoe and hitting me on the head with it.

It wasn't that bad. I continued to watch her to see if she was done. Then a strange look came over her face, and she turned and ran away.

As I turned back to my weeding, I felt something warm drip down my forehead and into my eye. I reached up to touch it, and when I saw the red of the blood on my hand, I screamed and ran inside the house.

The sight of my head and face covered with blood caused some excitement. My dad wrapped my head in a towel, picked me up and put me in the car. Then he drove fast to the hospital and rushed me in. When the doctor cleaned me up, he found a tiny cut, maybe a half an inch. He told my father that cuts on the head bleed a lot.

When my dad asked me why Molly hit me, I told him that I didn't know. Molly was sure she had killed me and so had locked herself in her room.

Of course I knew Michael the best of the Bobblettes because he was just about my age. I found him fascinating and disquieting. Michael was painfully skinny, with dark hair and sharp features. Living so close, we usually walked the four blocks to our neighborhood elementary school together. Usually he would do most of the talking, telling stories, often made up. He was dramatic and eccentric. He gesticulated with his hands, and used hard words. He was different from anyone else I knew, and yet this did not bother him. I just the opposite. I hardly spoke to anyone and avoided any extra attention.

A couple of years after Molly hoed me, when I was in the third grade, I remember how Michael entertained the other students by standing on a texture-coated bench on the gravel playground and singing opera in Italian. I assume it was Italian. All I knew at the time was that it was not English.

He sang with such exaggerated emotion that the kids who had gathered around him, could only stare blankly in disbelief. I watched from a safe distance, back in the crowd. I didn't want to be anywhere near the front where all the attention was focused.

Around that time, Michael asked me if I believed in Jesus. I didn't know what he meant. He said, "Do you believe that Jesus was the son of God?"

"No."

"Well, it's true, you know."

I had thought that this was a matter of opinion, upon which reasonable people might disagree.

He said, "No. It's in the encyclopedia. I looked it up, so it has to be true."

This had me stumped. I knew the encyclopedia was a very reliable source. Yet it seemed to be in direct contradiction to my parents, who were also a very reliable source.

I told Michael I'd have to discuss this matter with my parents. When I did, they said Michael must have been looking in some special Catholic encyclopedia. They said a regular, non-Catholic, encyclopedia would say that some people "think" Jesus was the son of God. And it would also say that some people didn't think so.

I accepted that.

I was in the third grade that year, and my teacher was Mr. Zert. He was the only male teacher at Victoria Elementary School, was in his early thirties, and wore a stylish mustache.

Though my previous teachers had never been mean to me, school was like a strange competition at which I was not good. School work appeared to be much easier for other students than it was for me. My discomfort about school included academics, sports and making friends. But I tried my best since I did not seem to have any choice about being at school.

Mr. Zert started in on me right away. The first day he asked me how to pronounce my name (all my teachers did this). Then he asked me what my middle initial, "P", stood for. I imagine he was hoping for a more familiar name like Paul or Pat. When I told him the P stood for Pessach, he let the matter slide. The next day, when he called roll, he had solved the problem. He pronounced my name, "Elisha P. Shapiro," as if it was written, "Elisha Peesha Peero." He almost sang it, accentuating the rhyme with obvious pleasure.

One day there were three of us standing at the board. We had to add 647 to 294. Standing next to me was the smartest girl in the class. The smart girl finished. Then the other guy finished. Everyone waited for me. When I was done, I was the only one who had the right answer. Mr. Zert earnestly asked me how I achieved the sum. My complicated explanation went something like this. First, I had to add the 7 and the 4. Well, I know that 7 and 3 made 10, so that left one over. I put the one down and then added the 9 and 4 and the one from the ten I just got. Well I knew that 9 and 1 is 10, so I had 3 left over from the four and one more from the 10, which made 4. So I put that down. And then I finished the last column similarly.

Mr. Zert seemed impressed, and told the class I had a good way to add the numbers, and that it doesn't matter if it took me longer because I got the right answer. I was a proud boy.

A game we played a lot was called French dodge-ball. It is played on a basketball court with two teams throwing balls at each other.

On my team, just two of us were not "out" yet, and our opponents were throwing hard, trying to get us. We were cornered. The ball was thrown. I ducked, hitting the asphalt, and my remaining team mate jumped over the ball. The ball missed us both, but when my team mate came down, he landed on my finger.

It took me a while to notice what a bloody mess my finger was. It didn't hurt much, but it looked very odd and misshapen. Another boy took my arm. "We better go to the nurse's office."

I followed obediently. As we sped along the institutional walkways, up ahead we saw Mr. Zert. "He'll know what to do." said my companion.

As we approached, we saw our teacher was in the center of a circle of young girls. Then we could see he was intently playing a game of cat's cradle with one girl as the others watched.

We edged into the circle, me holding my mutilated ring finger for all to see. The girls made way for us.

"Mr. Zert?" I peeped.

"Can't you see I'm busy." he snapped, eyes still riveted to the string cradle.

I sheepishly retreated, and we went the rest of the way to the nurse's office on our own. My parents came and took me to the doctor who repaired my finger.

The next day, with finger bandaged, I returned to school. After class started, Mr. Zert quietly came to my desk.

"Elisha, I'm sorry I didn't help you yesterday. I didn't see you were hurt."

"It's okay." I was not use to teachers talking to me this way.